Joshua trees in Tikaboo Valley, Nevada (jby)

This post is by JTGP collaborator Jeremy Yoder, an Assistant Professor in the Department of Biology at California State University, Northridge, who studies ecological and evolutionary genetics.

Since we first launched the Joshua Tree Genome Project, we’ve told you that one big reason we want to sequence a Joshua tree genome is to find genes that are important for adaptation to climate, which could help us makes sure that Joshua trees survive and thrive in a climate-changed future. But we haven’t discussed in detail how we’ll find those climate-adapted genes. The key to that part of the project is association genetics, a method for sifting through the genome to find the parts that contribute to traits we care about.

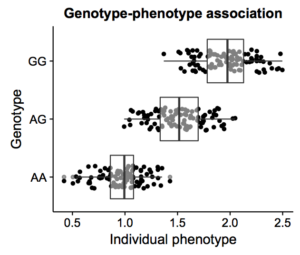

Figure 1. An example of a “candidate gene” experiment testing whether different diploid genotypes are associated with different trait values, or phenotypes. Points are the phenotypes of individual trees, grouped by their diploid genotypes at a candidate gene; overlaid box plots show that trees with different genotypes differ strongly in their phenotypes. (jby)

To understand how association genetics works, first consider a case in which we already know of a gene that might be important for a particular Joshua tree trait, like height or flower shape or physiological performance — or even just growing in places that are hotter or cooler. To figure out whether different variants in the sequence of our “candidate gene” are related to differences in the trait, we could measure the trait in many trees and then sequence that gene in all of those trees. We would test the hypothesis that the gene shapes the trait by comparing the trait values of trees carrying different variants of the gene sequence. Figure 1 gives an example of what this might look like in a hypothetical case, with tree phenotypes plotted against diploid genotypes at our candidate gene — “homozygous” trees carrying two copies of the G variant have higher phenotype values than homozygous trees carrying two copies of the A variant, and “heterozygous” trees with one copy of each have intermediate phenotypes. In this case, we’d probably conclude that the candidate gene has some effect on the phenotype we decided to measure, because different variants of the gene are associated with significantly different phenotype values.